- Home

- Malcolm Bosse

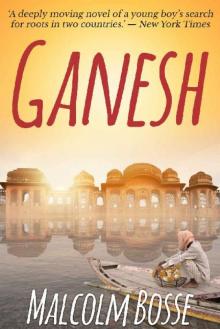

Ganesh Page 2

Ganesh Read online

Page 2

Now Jeffrey was no longer confident. He was frightened by the look of his father, who in one day seemed to have lost a great deal of strength. Were his father and the doctor telling him the truth?

That night he ate with Father in his bedroom. Holding plates of rice and spiced okra on their laps, they swirled the food around with the fingertips of their right hands, Indian fashion.

Abruptly Jeffrey said, “Tell me the truth, Dad.”

Sitting cross-legged on the bed, Mr. Moore began to smile in his typically cheerful way.

“Dad. Please.”

“You mean about my health?”

“The truth, Dad.”

Mr. Moore stared at him, then slowly lowered the plate and set it on the bed. “All right, the truth, Ganesh. The truth is I took the time on this last pilgrimage to have a checkup.” Mr. Moore looked down at the plate.

Jeffrey waited, feeling sweat begin to pour down his face.

“I do have a problem,” Mr. Moore continued softly. “The heart muscles are progressively weakening.”

“What does that mean? Is it serious now?”

“Far from it.” Mr. Moore’s voice was cool, steady. “Eventually, over a period of time, the muscles will lose their strength.”

“Over a period of time? When?”

“No one can say,” Mr. Moore replied with a smile. “Only Tibetan monks know the exact hour they will die — and that’s because they go into a death trance. They choose their time with deliberation.”

“But what’s a period of time?” Jeffrey persisted impatiently.

“Look, son, if I take care of myself, I should be around long enough to see you grown and educated. That’s the truth, Ganesh, as far as I or anyone else can know.”

“You should have told me about the checkup,” Jeffrey said reproachfully.

“I meant to. I would have, only I’ve been home just a week, Ganesh.” He laughed faintly. “Give me a break.”

Jeffrey repeated his father’s words to himself: “I should be around long enough to see you grown and educated.” Jeffrey felt a little better and relaxed his hands, which he now realized had been balled tightly. “Well, you must take rest,” he told his father.

“I will.”

“You must not go to the fields at midday.”

“I won’t. You’re right.”

“You must take a midday nap.”

“I will. I intend to do that. Now let’s finish dinner.”

They did, and Jeffrey took the plates out to the kitchen, where the housekeeper, a wiry, little woman with gray hair, took them with a frown. She was always frowning. She never even smiled when she was paid.

When Jeffrey returned to the bedroom, he took a pillow with him — his own — to put behind his father’s head.

Mr. Moore protested, then acquiesced with a smile. “Tell me, Jeffrey —” His father seldom called him by his Western name; between them it was more intimate than Ganesh, which everyone called him. Jeffrey leaned forward. “All these years I’ve been following Swamiji around on the pilgrimages, what did you really think?”

“It was something you had to do.”

“Really? You were never angry?”

“Sometimes I was lonely,” Jeffrey admitted.

“But not angry?”

“No. You had to do it.”

“Do you understand why?”

“No,” Jeffrey said with a grimace. “I don’t like Swamiji.”

“Yet you weren’t angry when I followed him?”

“No. You understand him. I don’t.”

“Jeffrey, let me tell you something. I no longer fear death. I no longer cling to life. But I have not lost my desire to be your father. Forgive me for times when I neglected you. I wouldn’t do it again. What’s so clear to me now wasn’t before.”

“I don’t care about the past,” Jeffrey said. “I just want you to take rest.”

*

For the next week Jeffrey went to school and Yoga class, while his father gradually resumed activity. Evenings they ate a simple meal of spiced vegetables and rice, then sat outside on the warm earth to watch the stars. Mr. Moore knew a lot about astronomy — indeed, he knew a lot about many things — so Jeffrey sat with him under Orion and Canis Major and listened to him expound theories about the universe, its birth, possible death, and rebirth. It was quiet in their compound, with only the hoot of owls to intrude upon their conversation or sometimes the irritable squeak of bats hanging upside down from the peepul tree. Not that the village was so peaceful outside their compound. On the main road at night there were radios playing at high decibels from almost every tea shop and milk kiosk, a constant whine of scooters, a babble of merchants around the stalls. And in village temples the priests were chanting and ringing bells to awaken the gods; from loudspeakers outside the temples poured the taped sound of devotional songs.

But in the small compound Jeffrey and his father had the broad night sky to themselves. What Jeffrey had told his father was true: he had never begrudged his father those long trips with the Swami in search of God; it was something a great man might do, and his father was a great man. Jeffrey knew this, although other people often did not. Father’s acquaintances in Madras — all Westerners — had drawn away from him when he began wearing dhotis and trudging the lanes of India with a staff in hand, his sandy hair covered by a rag. Jeffrey did not understand his father either. What was a search for God, when people took to the road and followed an idea that led them nowhere, half-starved, weak, without the slightest comfort? In this village, when people sought God, they visited a Hindu temple or the Catholic chapel near the school and merely said prayers, whereas Father and other devotees exhausted themselves on the hot paths, with only a handful of rice for their daily meal. Yet Jeffrey had accepted his father’s way, because that way was one of determination and courage. Jeffrey knew this and felt all right about it. And each evening that they sat together under the stars, he felt possessed by the energy of his father’s presence. It seemed that nothing could break the bond between them, especially now that Father must stay close to the village. Rest would strengthen the heart muscles; Jeffrey was sure of it. Nothing ever again would stop them from sitting together under the stars in their tiny compound, walled off from the noise of the village, from the whole world.

Then one afternoon at school a neighbor appeared at the classroom door. He was a retired postal worker who had always been kind to Jeffrey. Bowing to the schoolteacher, he said, “That boy’s father,” and pointed to Jeffrey, who suddenly felt numb. While returning home on the back of the old man’s bicycle, Jeffrey learned what had happened. There had been another “flare-up.” That morning Mr. Moore had driven twenty kilometers on his scooter to inspect some irrigation ditches near a hamlet. He collapsed in a paddy, and farmers brought him home in a bullock cart.

Arriving at the compound, Jeffrey rushed into the house. The doctor had been there, but was gone now — so whispered the housekeeper to him at the front door. Father lay panting in his bedroom. Seeing his son, he waved feebly. “I was not out at midday,” he said breathlessly. “It was morning. I kept my promise.”

“Don’t talk,” Jeffrey urged. “Just take rest.” Then forgetting his own words, he asked, “What did the doctor say? What happened? Does he know?”

Father smiled faintly. “Just a flare-up.”

“Oh, it’s more than that,” Jeffrey sobbed.

“Don’t worry, Ganesh, I have my pills.” His father looked at the box on the little bedside table. “At the time of my checkup I got them. They’re all I need.”

“Don’t talk, Dad, please. Take rest.” Jeffrey pulled up a chair and sat quietly until his father fell asleep. Then he went outside and sat under the peepul tree. Who was around to help? He would send a letter to Swamiji anyway, that’s what he’d do: “Come with help; my father’s awfully sick; he has always been loyal to you, now it’s your turn to be loyal to him!” Only he must not write without Father’s permission; it wouldn’t b

e fair. And would Father give it? No. Definitely not. Father would never disturb the Swami with such unimportant matters.

So who was there in the whole world to help? Who?

From across the yard came the retired postal worker’s wife, carrying a bowl. She was a very fat woman in a brown sari.

“Tender coconut,” she said, offering the bowl. “Have your father drink it. It is very good for the heart.”

Jeffrey got to his feet and accepted it with thanks. The woman meant well, but every time someone in the neighborhood got sick — a cold, rheumatism, typhoid fever — she came with a bowl of tender coconut. Jeffrey took the bowl inside and placed it on the table. Then he returned to the bedroom and stared at his sleeping father. One thing was sure: he would not leave the house again, not for school or Yoga or anything. If there was no one else to take care of his father, he would do it by himself.

*

So Jeffrey stayed at home to nurse his father. At dawn he went to the village well — they had no water in their own compound — to draw water long before the housekeeper came to work, so he could make tea for Father. In the heat of midday Jeffrey gave his father a sponge bath and brought in his lunch. In the afternoon he read aloud from one of his father’s philosophy books, to which his father listened intently, as if it were a rousing good story. And all through the day Jeffrey fussed with the bed sheets and pillows until his father laughed. That was something that surprised Jeffrey: how his father could still be cheerful while often in pain. Mr. Moore called Jeffrey “the little dictator” and pretended to fear his son, exclaiming, as he rolled his eyes, “Oh, my, oh, my, here he comes again!”

At night Jeffrey helped him walk slowly into the courtyard to sit against the peepul tree and look at the stars. Jeffrey never left him alone and learned to anticipate an attack — a so-called flare-up — by noticing the corners of his mouth twitch. Jeffrey would have a pill ready almost before he felt pain. Luckily the pills were effective, and within a few minutes brought relief. Each day the doctor appeared, but he was as useless as the people who came with home remedies, such as boiled nim leaves and the spiced core of plantain stalks. Still, Jeffrey was grateful for their coming. All day long they came to the broken gate of the compound with something: a few sweets, a homemade medicine, some fruit, a plate of cooked vegetables. It was clear that the villagers were impressed by Father, even if the Westerners in Madras had never been. These farmers and small traders understood the fortitude of a man who had walked the torrid roads of India seeking God. Now, at this time of crisis, they came with their simple marks of respect: food, remedies, a whispered inquiry about his health. Jeffrey forgot about the Swami. It was enough to have these people coming to the house, showing Father their respect.

Rama came every day after school. He was the son of a wealthy grain merchant, and Jeffrey’s best friend. Rama was small and thin, but could wield a cricket bat with boys twice his size. Sitting beneath the peepul tree at sunset, the boys watched chirping bats come looping in from somewhere, zigzagging with tremendous speed, barreling against tree limbs to hang like bunches of dark fruit and then whiz off again to catch insects in flight. The boys said little, but then neither was talkative. In better days they used to go swimming at a small lake and dive off the backs of buffalo who stood in the water to cool off during the afternoon heat. They hunted for sawscale vipers — fat-tailed, little brown snakes — who in spite of their size were aggressive killers, the cause of more snakebite deaths than any other species in the world. Farmers paid for the skins, each dead viper lessening their chances of stepping on a live one while plowing the fields. The two boys would climb banyan trees to scare monkeys, who merely scared them back, and stole plantains from the biggest grower in the district. They would stroll down country lanes and squint silently at groves of bamboo and green parrots balancing on telephone wires and watch the monsoon clouds come in like swirls of mud thrown across the bright blue sky. They were friends because they did things together, with one mind.

It was during one of Rama’s visits that Mr. Moore had such a serious attack that a single pill didn’t work — it took three to give him relief. Rama ran for the doctor, while Jeffrey stayed at his father’s bedside, holding his cold, trembling hand, watching in agony the agony of the haggard face. When the doctor arrived, he did nothing but listen through his stethoscope. Then he shook his head gravely and declared that luckily the pills had taken effect.

Jeffrey went outside with him.

Rama was waiting there. “I am going now, Ganesh.” They spoke English together.

Jeffrey nodded, although hating to see his friend leave. Still, it was right that he talk to the doctor alone.

“Sir, can my father go to Madras?”

The doctor pursed his lips without replying.

“Can it be done? Can I get him there?” Jeffrey persisted.

“I think it unlikely.”

“What do you mean?”

Again the doctor paused. “I think it unlikely that your father would survive the trip. Let him rest here.”

“But — isn’t there something I can be doing?”

The doctor, who had avoided Jeffrey’s eyes, now looked straight into them. “No, son, there is not. Let your father stay where he is. It’s what he wants.”

“How do you know?” Jeffrey asked bluntly, having forgotten to be polite. “How can you be knowing a thing like that!”

Quietly the doctor said, “Because he told me. Yesterday he said if it gets worse, he’d rather stay here than try for Madras.” The doctor touched Jeffrey’s arm. “You see, a man feels better in familiar surroundings.”

There were tears in Jeffrey’s eyes, coming into his vision. “You mean, when he’s dying? Is that what you mean?” He could not see the doctor clearly. “Is it? Is that what you mean?”

Again the doctor touched his arm. “Yes, it is. It is exactly what I mean, Ganesh.”

Jeffrey wiped the tears away as the man turned and left. For a while Jeffrey stood in the courtyard, trying to get control of himself. Suddenly he thought of his mother’s final illness. That had been terrible, but he had been a child then. This was worse because he was older, because no one stood between him and what was happening, as Father had stood between him and mother’s death. So he fought despair alone in the gathering twilight. Then, finally, he returned to his father’s bedroom, smiling.

“Well, the doctor says —”

“I know.” Father’s voice was scarcely a whisper. “I know what he says.”

“He says you must take more rest.”

“Ganesh, sit down.” He patted the bed. “It is time for more truth.”

Jeffrey sat down, trying to smile.

“I love you, son. But the truth is, I am not going to be with you a lot longer.”

“That’s not true!”

“It is. We both know it. Don’t we?”

Jeffrey felt his lips trembling so violently that he couldn’t speak.

“There are things,” Mr. Moore said, “we must say now.”

“Don’t talk, Dad. Take rest; we will talk later.”

“Now, Jeffrey. Listen to me. In the table drawer I have put some instructions for you to follow.” Mr. Moore paused for breath. “Through the years I set a little money aside for your future. Well, the future is now. Follow my instructions. They’ll take you —” Again he paused. “To a man in Madras who’ll make arrangements.”

“For what, Dad?”

“For going to America.” Mr. Moore placed his trembling hand on Jeffrey’s arm. “Your aunt has always wanted you to live with her.”

Jeffrey knew this. His aunt, a widow, often wrote and pleaded for him to come to America.

“I want you to go,” said Father.

“I don’t want to leave you or India.”

“Dear Jeffrey, I am going to leave you whether we like it or not.”

Jeffrey could hold back no longer; he put his head in his hands and sobbed.

“Look, son, I tol

d you I’m not afraid of dying. You alone worry me. I want you to leave here for a while. For education, experience. Come back later —” He paused for breath. “But after trying another life. You owe it to yourself. I promised your mother —”

“I don’t want to leave.”

“Promise you will follow my instructions!” Mr. Moore raised up on his elbows, panting, his face ashen and contorted.

Jeffrey, frightened, begged him to lie back. “I promise,” he said hastily. “Now take rest. Please! I promise!”

Mr. Moore sighed and fell back against the pillows. Then he winked at Jeffrey. “I trapped you, didn’t I. I took unfair advantage. Just the same, you promised. Jeffrey, you promised!”

*

A week passed without anything eventful happening, without a single attack, so that Jeffrey regained his hope. Father was in good spirits too, as if suffering from nothing more than a summer cold. He rested quietly through the day, and at night, holding Jeffrey’s arm, he shuffled outside to sit under the peepul tree. Once he said, “I can’t blame you for disliking Swamiji. He took up time I should have given to you. Now I no longer need him. But it took years for me to learn my answer is not in him but in myself. And in you, Jeffrey, and in the bats flying around, and the farmers of this village, and in whoever is laughing out there. We are all the same consciousness.”

At another time he said, “Remember this, Jeffrey. The soul is a bird. The nest it makes is the body. A bird makes its nest, raises its fledglings, then flies away. The nest rots, but the bird has made another nest. That is life and rebirth, son. Forgive my lecturing you, but there isn’t time to come to things naturally.”

Ganesh

Ganesh